Born in Ocala, Marion County, Florida, on October 31, 1893, Wiley Burford was the second of three sons among five children of Robert Allen Burford (1856-1938), a prominent attorney originally from Dixon Springs, Tennessee, and Ella Louise Murphree (1862-1945), of Troy, Alabama. Both of his brothers would also serve in the military during the Great War. Robert Allen Burford, Jr. (1887-1927), a Naval Academy graduate (1907), was a Lieutenant Commander aboard the USS Dekalb, a former German ship converted into a troop transport, and a naval recruiter in Atlanta (1919), while Samuel Kemp Burford (1896-1953), a graduate of Georgia Tech, enlisted in the Navy in July 1918 and held the rank of Machinist Mate Second Class on the destroyer USS Waters prior to his discharge six months later. In 1900, the Burford boys were all residing in Ocala, along with their parents and their two sisters, Mary Elizabeth (1889-1973) and Agnes (1900-1993).

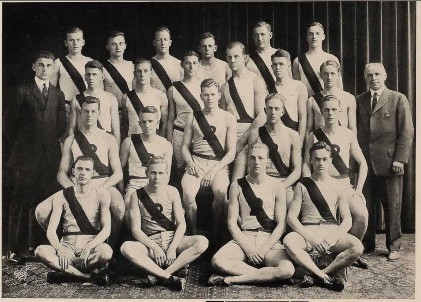

Wiley Burford went to Ocala public schools, including Ocala High School, where he was active in sports—track, football, and baseball—and a member of the Agatheridan Literary Society. After graduation with honors in 1912, he was accepted for admission to Princeton University, where his paternal first-cousin, Leo Bashinsky of Troy, Alabama, was in his junior year. While at Princeton, Burford (or “Burf,” as he was known), was a member of the Southern (heritage) Club, the Cliosophic (debating) Society, and the Florida (social) Club, and he served as treasurer of the Tower (eating) Club. He also was on the freshmen gymnastics team, the rifle team, club baseball team, and the intercollegiate varsity track team, competing in the broad jump and pole vault events against other Ivy League athletes.

After earning his bachelor’s degree with honors from Princeton in May 1916, Burford joined some 230 other Princeton students —about 15% of the male-only student body—in attending a 5-week-long military preparedness training camp at Plattsburg, New York, with Regular Army instructors. Of the eight thousand young men enrolled over the summer of 1916 at the Business Men’s camp at Plattsburg, about half were college students, mostly from Ivy League schools. Burford praised the experience highly, saying that the military training he received was “no picnic.”

Afterwards, in the fall of 1916, he entered the University of Florida law school, following in the footsteps of his father whose practice he intended to join upon completion of his degree. At Gainesville, law school suited him. He excelled his first year, ranking in the top ten percent of his class. He was president of the John Marshall Literary Society and a member of the intercollegiate debating team that defeated both the University of South Carolina and the University of Tennessee. In the debate against the South Carolina team, Burford argued in the affirmative that immigration should be restricted by a literacy test. Burford was also a member of Kappa Alpha fraternity, the Serpent Ribbon dance society, and the Cooley Club, an honorary legal fraternity. And he was junior class president for 1916-17. But rather than finish law school the next year, he decided to forgo his senior year to answer his country’s call to arms.

National service was a Burford family tradition. Wiley’s grandfather was a veteran of both the Mexican War and the Civil War. His great grandfather served under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. And his third great grandfather was a captain in a North Carolina regiment during the Revolutionary War. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, one of army’s most pressing needs was a trained officer corps to lead an expeditionary force to fight in France. To achieve this goal, the army chose to establish a series of Officer Training Camps (OTC) to commission officers. By the end of the war, almost half of the army’s officers were products of such camps. The first of these camps for men in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama was held at Fort McPherson, near Atlanta, Georgia, beginning May 15. Then twenty-four years old, Burford applied for admission and was accepted among the first 2,500 candidates into the 3-month program. A score or more of University of Florida students also attended the camp. On August 15, 1917, he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant, Artillery, Officer Reserve Corps, U.S. Army.

While training to become an officer at Fort McPherson, Georgia, Wiley Burford registered for the draft on June 5, 1917.

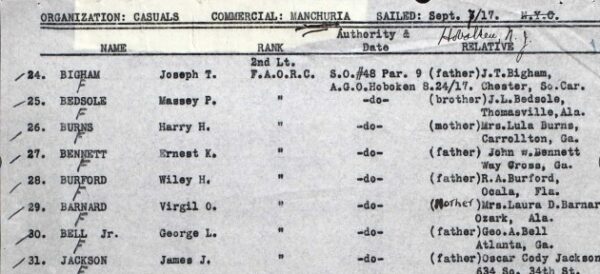

Manifest of September 7, 1917, for the SS Manchuria, listing Second Lieutenant Wiley H. Burford. The “F” stood for France, Burford’s ultimate destination.

By 3 pm, September 7, 1917, Lieutenant Burford was among more than 280 other reserve officers aboard the passenger liner SS Manchuria heading from Hoboken, New Jersey to Liverpool, England via Halifax, Nova Scotia. Arriving in France on September 22, he was ordered to the newly-established Field Artillery School of Instruction at Saumur, overlooking the Loire River in western France. As a reserve officer with limited experience, Burford badly needed additional theoretical and practical training to ready him for the technical work of an artillery battery commander in the A.E.F. The capacity at Saumur during the first training camp while Lieutenant Burford was enrolled there was set at about 500. The course was for twelve weeks and covered such topics as artillery matériel, ammunition, and ballistics, reconnaissance, topography, and camouflage, battery mounted telephones and wireless signaling, as well as observation of fire, methods of fire, and a considerable amount of conduct of fire with French-supplied 75-mm. guns, popularly known as the “soizante-quinze.” Since a typical American artillery battery, consisting of 5-6 officers and approximately 190 men, was comprised of as many as 160 horses used to transport artillery, ammunition, and supply wagons, instruction at Saumur also included horsemanship and equine veterinary management. Lieutenant Burford did well at the school, earning a Grade “A” certificate denoting efficiency. One of his instructors noted that Burford was both “energetic and ambitious; a good worker and very intelligent. He made great progress here.” He finished the course on December 28, 1917.

Originally detailed to Headquarters, 1st Brigade, 1st Division, A.E.F., on January 1, 1918, Lieutenant Burford was assigned the following day to Battery A, 7th Field (Light) Artillery. Organized in July 1916 at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, the 7th Field Artillery became the following June part of the 1st Expeditionary Division, the advance guard of American fighting men going to France. Together with the 6th Field Artillery and the 1st Trench Mortar Battery, it formed in July 1917 the 1st Field Artillery Brigade. By mid-December, the 1st Field Artillery Brigade had undergone strenuous training by French instructors at Valdahon, an old French artillery post, and had been brigaded with French artillery units on the Lorraine front. It also had experienced its first casualties, owing to a deadly combination of enemy sniping, artillery fire, and night raids.

Lieutenant Burford finally joined the 7th Field Artillery in early 1918 after it had been relieved and pulled back from the front lines, as it was camped in the Gondrecourt area in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department in northeastern France, between the Saulx and Ornain rivers. The 7th’s commander was Col. Lucius Roy Holbrook, a West Point graduate (1896), and a veteran of the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, and Mexican Expeditionary Force of 1916. Holbrook was perhaps best known as author of the army’s first cooking manuals, inventor of the army field oven, and founding commander of the army’s training school for bakers and cooks. Yet he had transferred from the Commissary to the Artillery branch and had led the 7th Field Artillery since its organization at Fort Sam Houston. Commanding Battery A was First Lieutenant Gustav Henry (“Gus”) Franke, Jr., who had graduated 12th out of 83 in his class at West Point in 1911. On October 22, 1917, Franke’s Battery A had the distinction of firing the first American artillery barrage against German forces as his unit moved forward in the Sommerviller sector. Franke would retire from the Army as a major general in 1944.

Scene from a film showing men from the 7th Field Artillery Regiment firing a French 75 mm. gun near Beaumont, Ansauville sector, January 1918.

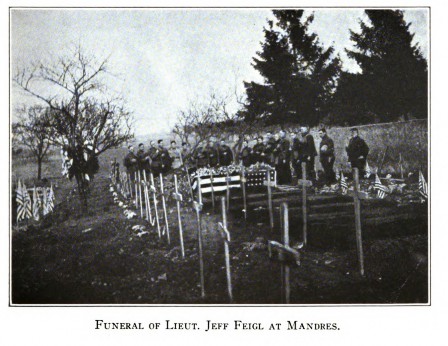

In January 1918, the 7th Field Artillery moved from Gondrecourt into the relatively quiet Ansauville sector and set up defensive emplacements along the road near Beaumont. Less than a month later, on February 12, Lieutenant Burford was wounded in an accident in the line of duty near Rangéval, some 12 miles northwest of Toul. He was evacuated by ambulance to Field Hospital No. 13, which was in some former French barracks at Ménil-la-Tour, about nine miles away. The nature of his injuries is unknown, but the date of his death is certain. He died on February 14, 1918. Two days later, a plain wooden coffin bearing his body arrived by ambulance at an American extension to an old cemetery behind Saint-Martin church in Mandres-aux-Quatre-Tours. Next came a truck loaded with soldiers from his regiment, followed by several officers from his and other batteries. As the regimental band played “Jesus, Lover of My Soul,” six soldiers carried Burford’s coffin to the grave, where a Catholic chaplain conducted a brief funeral service. With echoes of German artillery firing in the background, Lieutenant Burford’s coffin was lowered into the old burial ground and a wooden cross with his name and rank on it was placed on top of his grave.

Second Lieutenant Jefferson Feigl, Battery F, 7th Field Artillery, was buried on March 22, 1918, in the same cemetery as Burford, whose grave was a few feet away.

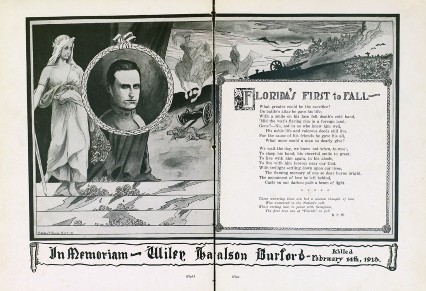

The suddenness of Wiley Burford’s death shocked everyone. The U.S. Adjutant General of the Army, Henry Pinckney McClain, in Washington, D.C., notified Burford’s father of his son’s death in a telegram on February 16, which read: “Deeply regret to inform you that it is officially reported that Second Lieutenant Wiley H. Burford, field artillery, died of a bullet wound” to the head. According to the Ocala Evening Star, the news of Wiley’s death spread through downtown Ocala “as swiftly as fire follows a train of powder,” taking “the smile off of every face.” The newspaper praised his sacrifice: “He died for America; he died for France; he died for right and justice and the welfare of the whole world.” His death, the writer hoped, would inspire reluctant volunteers, “whose feet are slow to enter the pathway of duty and honor.” The Ocaleean Ensign observed that Burford “was an ideal man, one of whom his hometown, his county, his state, the nation and even the world can be proud.” “His life was clean, upright and pure. He was brave and courageous, daring always to do the right and shirk the wrong.”

Other newspapers throughout Florida and the South echoed these sentiments. According to the Tampa Tribune of February 19, Burford died at the front where a “brave leader should be” and “we all have one more brave example of duty well performed, and a memory of manliness to be an incentive for our other boys.” The Miami Herald remarked in its issue on the same day that Burford was “a brilliant young man greatly beloved.” He was “gentle, tender-hearted, wholesome” who died “a soldier’s death on the field of honor in France.” The Troy Messenger, a newspaper in Alabama where his mother’s family resided, noted: “The young lieutenant was a man of great heart, and popular with a legion of friends.” And the Carthage Courier of Tennessee, where his father’s sister lived, said that Lieutenant Burford was “appreciated here . . . for study qualities, manifested by a quick mind and pleasant manners.”

Similar tributes from his classmates and faculty members poured in. “His cheerfulness, modesty and manliness marked him as a true friend and one for whom the future had much in store,” said Neville Miller, Class of 1916, Princeton. A Kappa Alpha fraternity brother wrote that Burford was a “highly intelligent, clean-living, brave, and courageous young man,” adding: “He did not want war and did not aspire to the life of a soldier. His inclinations and training were toward a life of peace and order. But he saw his duty, and went to meet it….He died for America; he died for France; he died for the right and justice and the welfare of the whole world; that wrong may be rebuked and mercy and safety may abound. God give us millions like him.”

Wiley Burford’s name, along with those of 150 other Princeton men who died in the Great War, is commemorated on this plaque located at the Pershing Hall, Paris, France.

At the University of Florida the 1919 Seminole yearbook was dedicated in his honor. A poem in the yearbook proclaimed Wiley “Florida’s First to Fall.” The student newspaper, The Florida Alligator, also paid respect to Wiley’s loss.