Born in Trenton, New Jersey, on April 18, 1890, DeGarmo graduated in 1908 from Ridgewood (N.J.) High School, where he played basketball and was advertising manager of the first issue of the school yearbook, The Arrow. Nicknamed “Diggie,” he was the class vice president, who gave an oration on graduation day, and he was considered “everyone’s friend.” The Ridgewood Herald described him as being a “slim chap of medium height,” with blond hair, blue eyes and “a splendid smile.” Always “nice to everyone,” he was active in the Ridgewood Y.M.C.A. and a member of the First Church of Christian Scientists. Diggie was the eldest of three DeGarmo boys who all graduated from Ridgewood High, and his was the first of seven names to be placed on the school’s World War roll of honored dead.

The DeGarmo family descended from French Quakers surnamed de Garmeux who settled along the Hudson River of New York by the 1780s. Diggie’s father, George Jay DeGarmo (1855-1943), originally from Ypsilanti, Michigan, operated a surgical appliance store in New York City before selling his company in 1920 and moving to Coconut Grove, Florida. One of George’s older brothers, William Burton DeGarmo (1855-1936), who retired in Coral Gables, Florida, was a physician who wrote a textbook on the mechanical treatment of hernias, and George manufactured and sold medical devices specifically for that purpose. In 1889, George married Sidney Wilson Eastburn (1867-1956), a daughter of a Pennsylvania farmer, who bore him three sons: Lindley; Elmer Coleman DeGarmo (1892-1973) and George Jay DeGarmo, Jr. (1898-1971).

Both of Diggie’s brothers would also serve in the Army Air Service during World War I. A graduate of ground school at the University of Illinois, Elmer was a second lieutenant stationed at pilot training camps at Carlstrom and Dorr Fields, both near Arcadia, Florida, prior to his discharge in January 1919. Born in Flushing, New York, George, Jr., served as a sergeant in the 341st Aero Squadron in France. During World War II, he commanded an aerial reconnaissance squadron in the Pacific. A pioneer in high altitude photography and mapping, George Degarmo, Jr., retired as a Navy captain in 1959.

Lindley’s youngest brother, George Jay DeGarmo, Jr., earned engineering degrees from Stevens Institute of Technology (1923) and Tulane University (1926), before founding his own aerial survey company in Farmington, New Jersey.

Diggie went on to attend Cornell University, where one of his second cousins, Charles DeGarmo (1849-1934), was on faculty. Born in Wisconsin, Charles DeGarmo earned his Ph.D. from the University of Halle in Germany, before serving as the fourth president of Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania (1891-98) and then joining the education faculty at Cornell University. Dr. DeGarmo was a prolific author of more than one hundred articles and books about educational theory and practice. As founding president of the national Society of Professors of Education in 1902, he was succeeded by John Dewey. Retiring from Cornell in 1914, he too moved to Coconut Grove, Florida, where his sons and their families also lived. One of his sons, Robert Max DeGarmo (1885-1922), also attended Cornell University, from which he graduated in civil engineering in 1909, Diggie’s sophomore year. From July 1917 to March 1919, he served in the 17th U.S. Engineers in France overseeing the construction of the docks at St. Nazaire, rising to the rank of major.

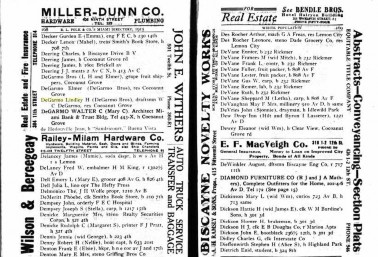

While at Cornell, Diggie became a member of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (A.I.E.E.) and the Cornell Rifle Club, an intercollegiate competitive team. “L.H.,” as the editors of the 1912 Cornellian referred to him, possessed “an energetic spirit and a jovial disposition,” both qualities predicted to carry him far in life. Following his graduation in June 1912, with a B.S. in mechanical engineering, he joined his father’s medical device firm in Brooklyn as vice president. By 1915, he had moved to Coconut Grove where he and his brother Elmer formed DeGarmo Bros., growing and shipping grapefruits. That same year he was working as a draftsman, while Elmer was a surveyor, for Frohling & DeGarmo, an architectural firm cofounded by another of Dr. DeGarmo’s sons, Walter Charles DeGarmo (1876-1951). After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania (1898) and Cornell University (1900), W. C. DeGarmo became Miami’s first registered architect, whose commissioned buildings included the Woman’s Club of Coconut Grove, Miami City Hall (1907) and Miami’s first skyscraper, the McAlister Hotel (1917), though he is best known for his residential work in South Florida, especially large luxury residences in the Mission and Mediterranean Revival styles.

1915 Miami directory, listing L.H. or Lindley as both grapefruit shipper and draftsman with W. C. DeGarmo.

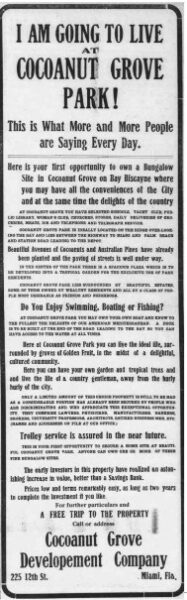

Cocoanut Grove Park, located between the highway and Douglas Road, was one of Coconut Grove’s first planned subdivisions, platted and designed in 1910 by Lindley DeGarmo’s cousin.

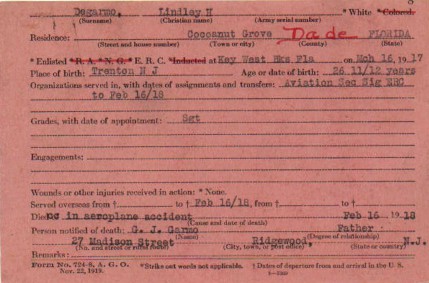

On March 16, 1917, less than a month before the United States declared war on Germany, DeGarmo joined the Army’s Enlisted Reserve Corps at Key West Barracks, Florida. More than anything else, Diggie wanted to learn how to fly. So, he volunteered for the Aviation Section of the U.S. Signal Corps (A.S.S.C.), the predecessor of today’s Air Force. In May 1917 he was one of three enlisted men to complete a pilot training course at the Curtiss Flying School near Miami, where he became certified to fly a Curtis Model JN “Jenny” 4-B Military Tractor, which was widely used for training in World War I. Then, the Army Air Service sent him to the preflight (ground) School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Texas in Austin. There were exams every week, for the next eight weeks, and pressure was intense. The most important function of the ground school was the elimination of those who did not give immediate promise of becoming good flying officers. Sergeant DeGarmo impressed everyone. Graduating the first in his class, he was one of five men selected from the UT-Austin program to attend primary flying school in England. On August 15, 1917, he was among the first detachment of more than fifty Americans chosen by Britain’s Royal Flying Corps (R.F.C.) for advanced training at Christ Church College of the University of Oxford. Officially, he was a sergeant in the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps. Practically, he was an American cadet, training in England with the Royal Flying Corps, which became in 1918 the Royal Air Force.

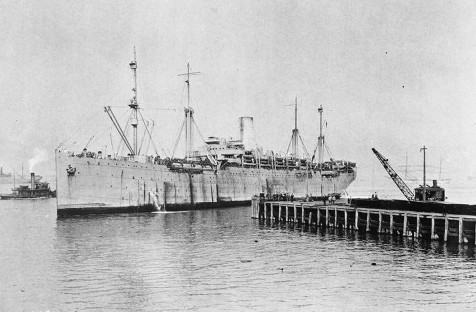

Sgt. L. H. DeGarmo aboard the ocean liner SS Lapland, built in Belfast, on his way to Liverpool, England, August 15, 1917. As shown above, the first lieutenant in charge of Christ College cadets was Geoffrey James Dwyer, a 1911 graduate of Columbia University with British parentage.

Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps, Enlisted Reserve Corps, A.E.F., training at No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics in Oxford, England, in the Royal Flying Corps, September-October, 1917. Sergeant DeGarmo is standing second row back, fourth from the left (enlarged, right). Lieutenant Dwyer is seated in the middle.

DeGarmo began ground school at Oxford on September 4. Classes ran from 8:30 in the morning to 7:30 at night. There were lectures on enemy aircraft identification, aerial bombs, artillery observation, wireless operation, as well as Vickers machine gun firing. Instruction was aided by photographs, lantern slides, model miniatures, and printed diagrams. Exceling at Oxford, DeGarmo was one of a handful of American pilots chosen for elementary flight school at No. 1 Training Depot at Stamford, Lincolnshire, on October 20, 1917, under Lieutenant Dwyer, who now oversaw the American Air Service Flying Training Department in England. From Stamford, about 85 miles northeast of Oxford, DeGarmo wrote home a month later, saying that he was doing “a lot of flying” with his instructor, and that he was the first American in his detachment to make a solo flight over England. He stayed up about an hour at 4,000 feet until his face nearly froze and he had to come down. It was a “great place to fly,” where he had gained a slight reputation as a “Stunt Merchant,” mastering the art of looping, spinning, and turning side flips. Regardless, he was well enough thought of to have published a pamphlet entitled “The Necessary Preparation for Aviators,” written in both English and French.

In late November 1917, DeGarmo was assigned to advanced flying school with the No. 56 Training Squadron, R.F.C., based at London Colney, Hertfordshire, a flying field just outside of London, where he continued his flight training on a variety of British and French aircraft —Avros, Sopwith Pups, and Spads— “the latest and fastest models, and ridiculously small,” which he likened to flying “little sticks of dynamite.” One of his roommates was Elliott White Springs, the son of a wealthy cotton-mill owner from South Carolina and a Princeton graduate, who became an accomplished fighter pilot, credited with shooting down twelve enemy planes and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Springs viewed DeGarmo as a rival. “There’s always been considerable competition between us,” Springs wrote his stepmother, “and we’ve been neck and neck until just recently when he got lost one day and while he was away I got in about six hours of flying time on a new type of machine.” Springs added: “We both looped for the first time on the same day — both spun for the first time on the same day, etc.”

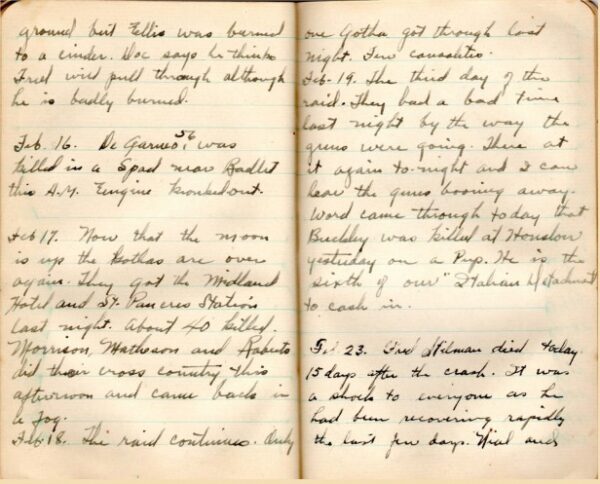

On the morning of February 16, Lindley DeGarmo went up in the same Spad S7 that Springs had flown the day before. In his diary, Springs wrote on February 15: “Flew a Spad to-day. Easy to fly but dangerous as hell, . . . it has the gliding angle of a brick.” Springs’s diary entry for February 16 begins: “DeGarmo was killed to-day.” He crashed in a small field near Ratlett on the outskirts of London while attempting a forced landing. Doing a right-hand vertical bank to avoid some trees, his engine stalled, and, like a crippled bird, he dropped out of the sky, hitting the ground hard, fracturing his skull and breaking his neck.

As his commanding officer, Geoffrey Dwyer, explained in a letter to DeGarmo’s parents, Cadet DeGarmo had completed all his required training and had been recommended for a lieutenant’s commission prior to the accident. Indeed, on the day after the accident, Diggie’s father received a telegram from the War Department that his son had been promoted to second lieutenant. The timing of that telegram was a “pathetic coincidence,” the Ridgewood Herald commented, but a “splendid tribute” to a fine flyer. His son’s death, George added, though a “fearful sacrifice,” was just as glorious had it come in battle in France. A fellow cadet said that DeGarmo was without doubt the best pilot in the squadron who simply “had no fear.”

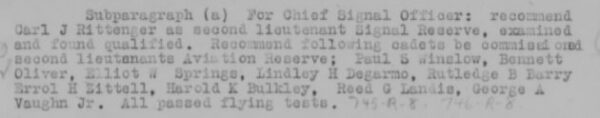

Memo recommending that Lindley H. DeGarmo, Elliott White Springs, and other RFC cadets be commissioned second lieutenants, dated January 29, 1918, having “passed flying tests.” Approved by General Pershing on February 8.

Diary entry of February 16, 1918, documenting the death of L.H. DeGarmo of Training Squadron No. 56, by Jesse Frank Campbell of Royal Oak, Michigan, another cadet.

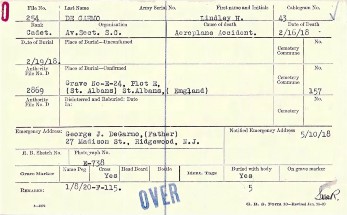

On February 19, 1918, Cadet Lindley H. DeGarmo, 28 years old, was laid to rest in Grave 24, Plot E, St. Albans (Hatfield Road) Cemetery, near the ancient Cathedral and Abbey Church in St. Albans, Hertfordshire, England. The whole squadron attended his funeral which was full of military honors, his coffin draped in an American flag and conveyed on a gun carriage. Meanwhile, someone packed up his personal effects into a trunk and suitcase and shipped them to DeGarmo’s parents, arriving several months later.

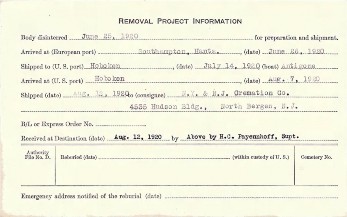

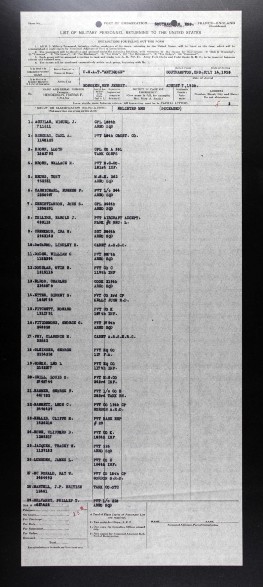

On June 25, 1920, Cadet DeGarmo’s body was disinterred and shipped from Southampton, England aboard the U.S. Army Transport Antigone to Hoboken, New Jersey, arriving at North Bergen, New Jersey on August 12, 1920. He was reburied in a plot reserved for his mother’s family in Riverview Cemetery in Trenton.

A month earlier, some 44 veterans in Coconut Grove, Florida, formed a new American Legion post which they named in Lindley DeGarmo’s honor. In April 1921, George DeGarmo donated the flag used to drape his son’s coffin to the post. About the same time, his cousin, Dr. Charles DeGarmo, wrote the following poem in his memory:

TO THE AIRMEN

Dedicated to Lindley DeGarmo

Thy country lives in thee when borne on wings,

Thou cleav’st the very heavens, for fears forgot,

Thou hast on patriot altars flowing hot

Made sacrifice of all that fair peace brings.

And now thy heart, like hers, exultant sings

Of Liberty through victory; ‘tis not

An age for tyranny – thy plunging shot

Shall help her blast the might of ruthless kings

And should’st thou hapless fall, why even then

Life of her life, thou’ll live in her, and she

Shall be thy bride, her children thine and when

She calls her roll of fame thy name shall be

Acclaimed among the names of Christ-like men

Who lived and died to keep their country free.

Manifest of the USAT Antigone carrying the flag-draped coffin of Cadet DeGarmo, #10 above, among other deceased enlisted men.

At Cornell, Lindley DeGarmo was remembered with the dedication of a memorial building on May 23, 1931, commemorating the University’s 264 students, alumni, and faculty from thirty-three states, the District of Columbia, and five other countries, who died in the war. President Herbert Hoover delivered a dedicatory address over a nationwide radio and telephone hookup broadcasted at 12:40 p.m. from his summer retreat in Rapidan, Virginia. “In this memorial,” the President stated, “as in all our other memorials, we do not seek to glorify war or to perpetuate hatreds. We are commemorating not war, but the courage and the devotion and the sacrifice of those who gave their lives for their fellows and for their country.”

DeGarmo’s name is carved on the walls of Cornell’s War Memorial that connects Lyon and McFaddin Halls.